Lovely story from The Guardian

It was September 2014. I’d just started working front of house in a fancy hotel in Edinburgh. I spent most of my shifts with a paper napkin pressed to my nostril, as I had been getting lots of nosebleeds. I would soon find out why.

A few weeks earlier, I’d been travelling in Vietnam. I had rented a moped and had the time of my life driving around. I soon crashed but luckily was wearing a helmet, so only got a small bump on my head.

A few days afterwards, I started to intermittently spot blood from my right nostril. I assumed it was from the crash and didn’t think too much of it. I was 24 and too busy partying to take anything like that seriously. I danced the nights away while ignoring the persistent blockage in my nose.

Reality came flooding back after returning to cold Glasgow. Nothing had changed with my nose, so I went to the GP. The doctor told me that it didn’t sound like anything to worry about. I was advised to use Vaseline on the area to keep the nostril lubricated and was sent on my way.

A week later, I moved to Edinburgh for my job. That’s when I started to feel frustrated with my constantly stuffy nose. I wasn’t in pain, but sleeping was difficult. I would blow my nose to try to clear the blockage, but it would only lead to nosebleeds. Things started to get particularly weird when I was having showers. Through all the humidity, I could feel a thick, slimy thing moving down my nose.

I had a day off work; it had been a month since I returned from abroad. My friend Jenny was coming from Glasgow to meet me for dinner. I was in the shower when I felt the all-too-familiar feeling, but this time I glimpsed something hanging out of my nostril. I jumped out and raced to the mirror, frantically wiping off the steam. I saw a clot hanging out – then recoiled in horror when I saw ridges running along a thick black body.

I rushed out of the house to see my friend, screaming, “It’s a full-on worm!” Jenny knew about the problems I’d been having with my nose, but she didn’t believe me at first. I stuck my nose in the air so that she could see for herself. Her mouth hung wide as she gaped and said: “Yep, there really is a worm in there.”

At first, it was the most hysterical thing that had ever happened to us. We couldn’t stop laughing. Because it had been in there for so long, I felt very blase about the whole thing. We rang the NHS helpline. The call adviser was crying tears of laughter over the phone, as it was the most bizarre thing she’d heard.

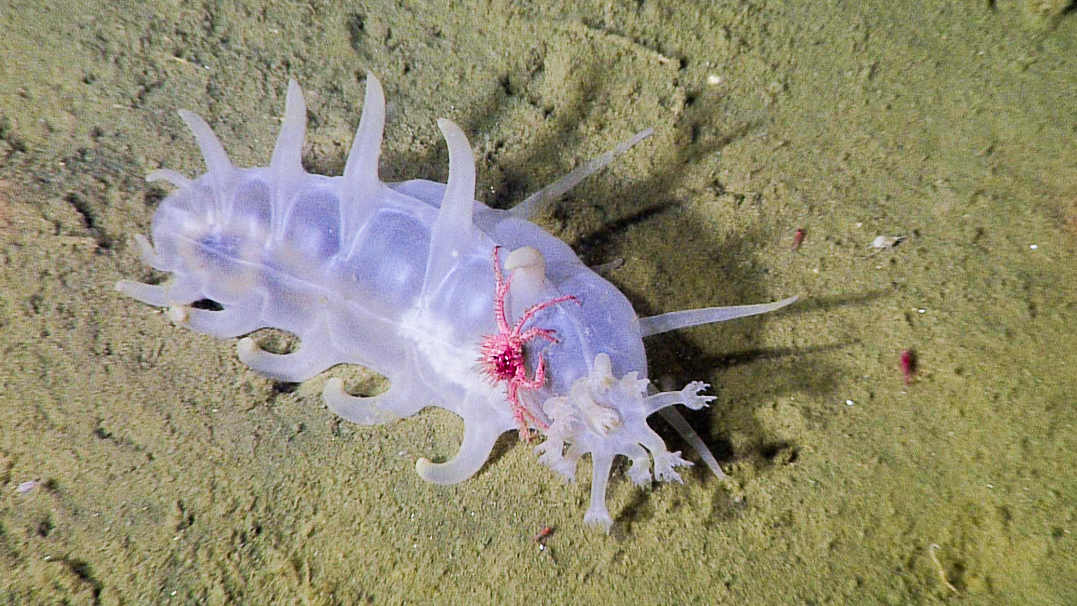

We went to A&E. Doctors were bewildered and didn’t take me too seriously at first. But once the nurse looked up my nose, she gasped. I was placed on a gurney as they stretched my nostril open with forceps. The doctors spent 30 minutes using different tools to try to prise the leech away. Leeches release an anaesthetic when they bite so they can stay on a body for longer, which is why I couldn’t feel the pain before – but it was agony when the doctors tried to pull it out. When they finally succeeded, I felt a wave of cold air shooting through the blocked nostril. It was like being in a nightmare, seeing the leech held up high, squirming. It was longer than my finger.

I’d swum a lot on holiday, so we guessed that it most likely came from there rather than having anything to do with the motorcycle accident. The leech was put in a jar and sent to a specialist hospital in London for further testing – they were worried that it may have passed on further diseases to me. Suddenly, something that was so funny seemed much more serious.

Luckily, all of my tests came back clear, and I had no side-effects. I was given the leech back in a pot and told to dispose of it. The leech was rock hard because it had so much of my blood inside. It made me squirm just looking at it.

Now, a decade later, the story of the leech and me has become a go-to anecdote whenever I meet someone new. I even had someone message me on LinkedIn recently asking about it. So while the leech was attached to me in a very physical sense, I guess we’re still attached metaphorically. But I’m very glad it’s out.

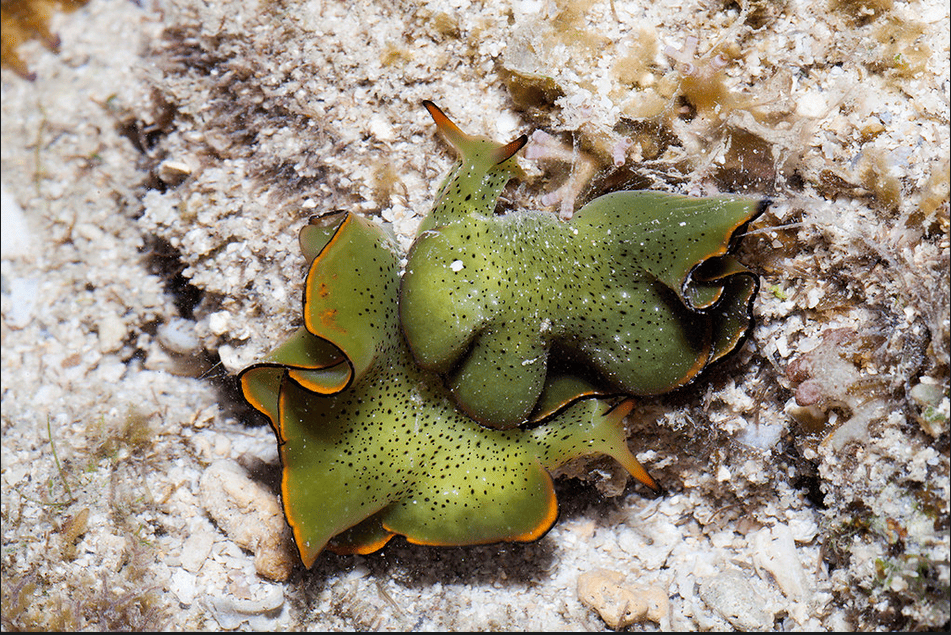

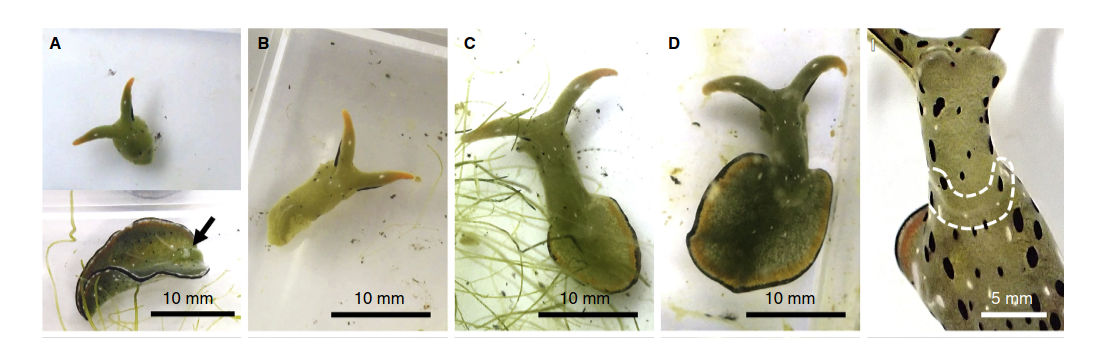

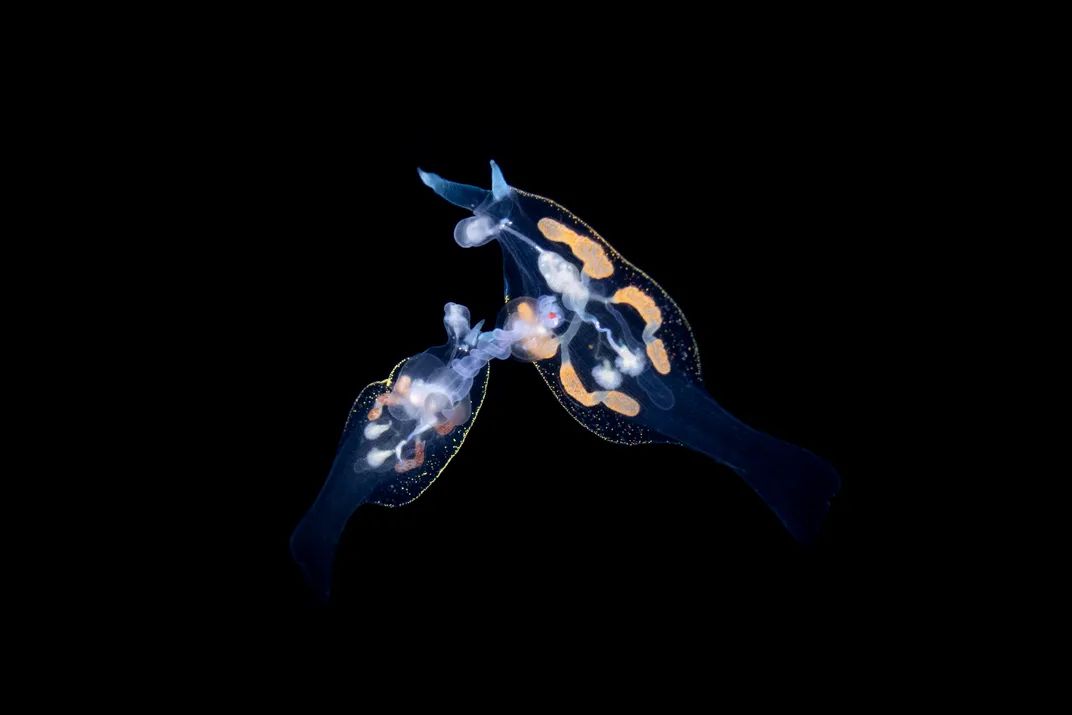

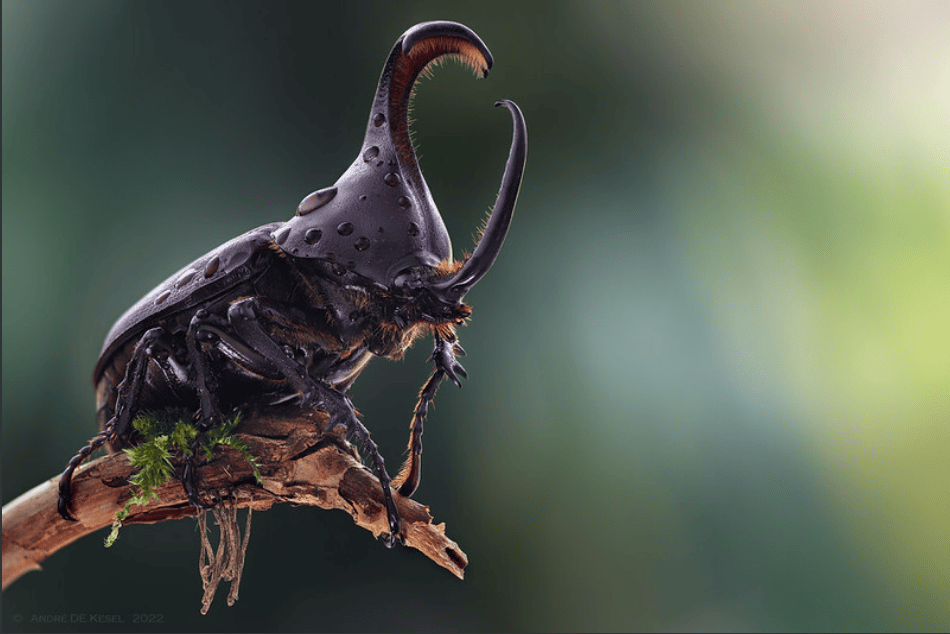

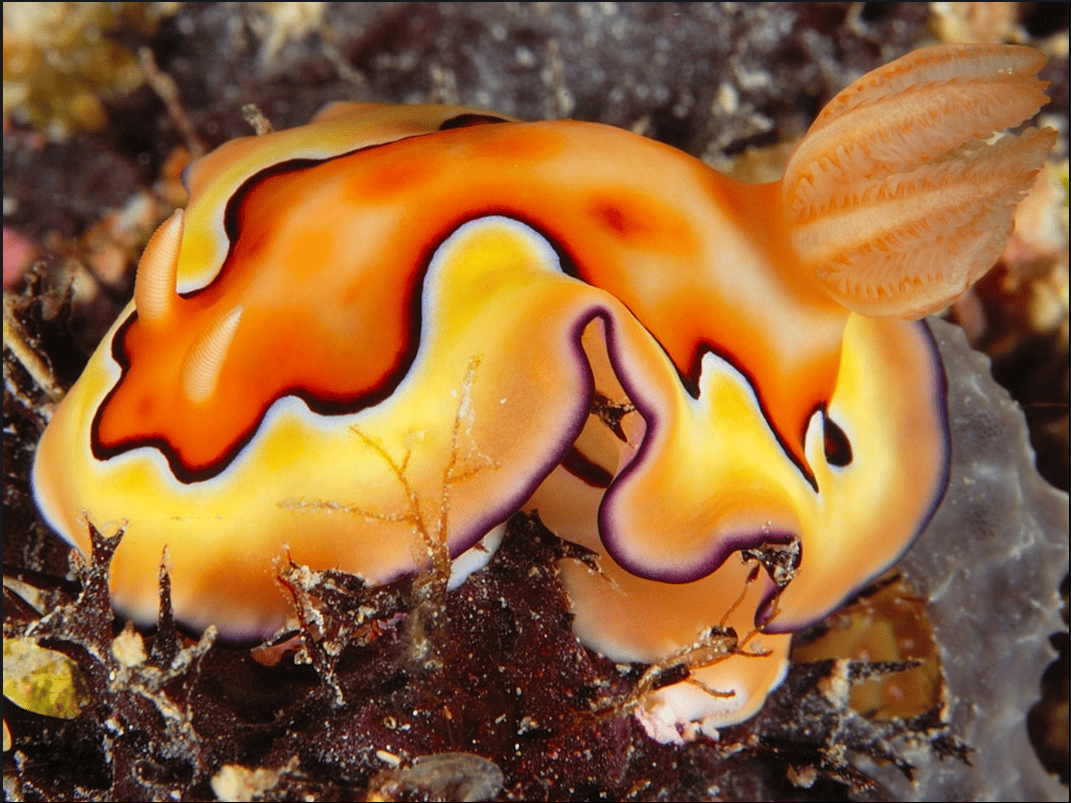

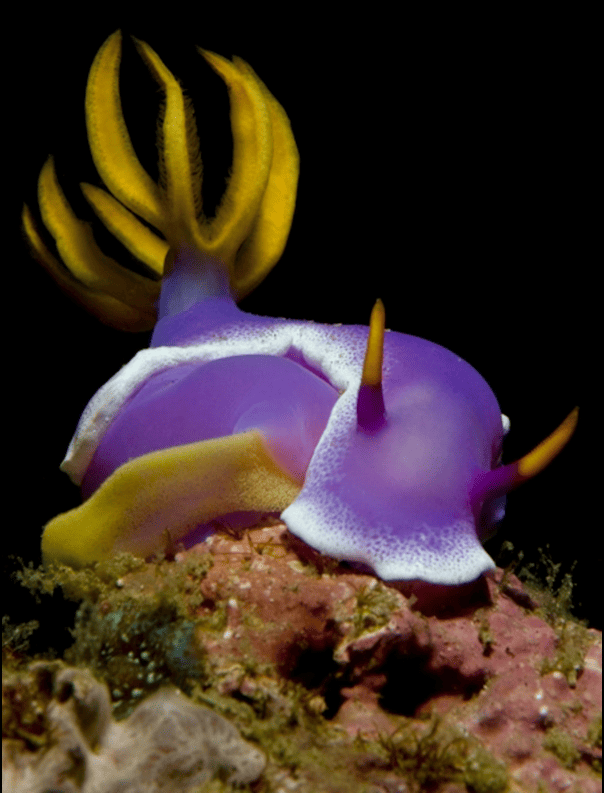

Link to an earlier post about shrimp jockeys....

https://mander.xyz/post/11798834

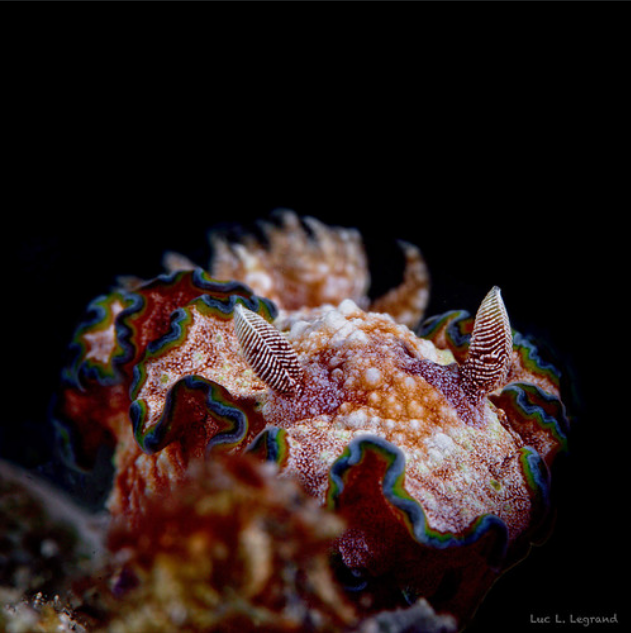

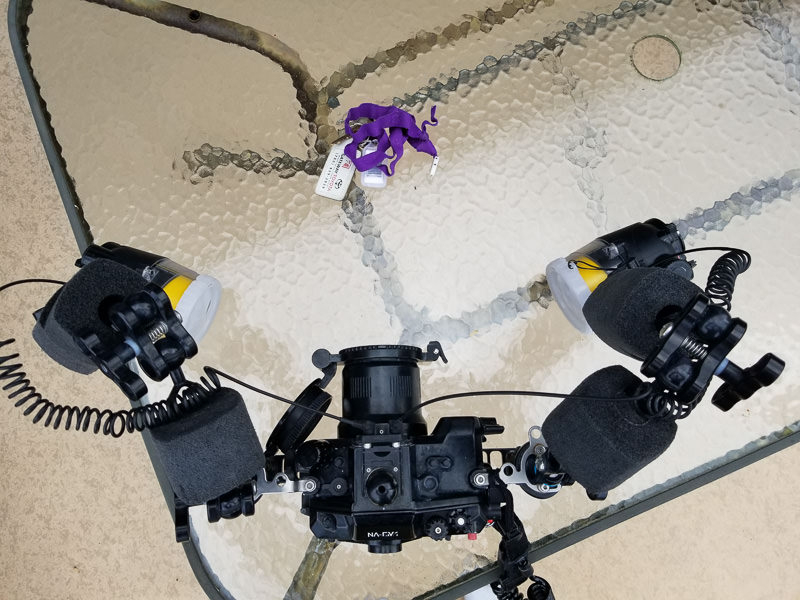

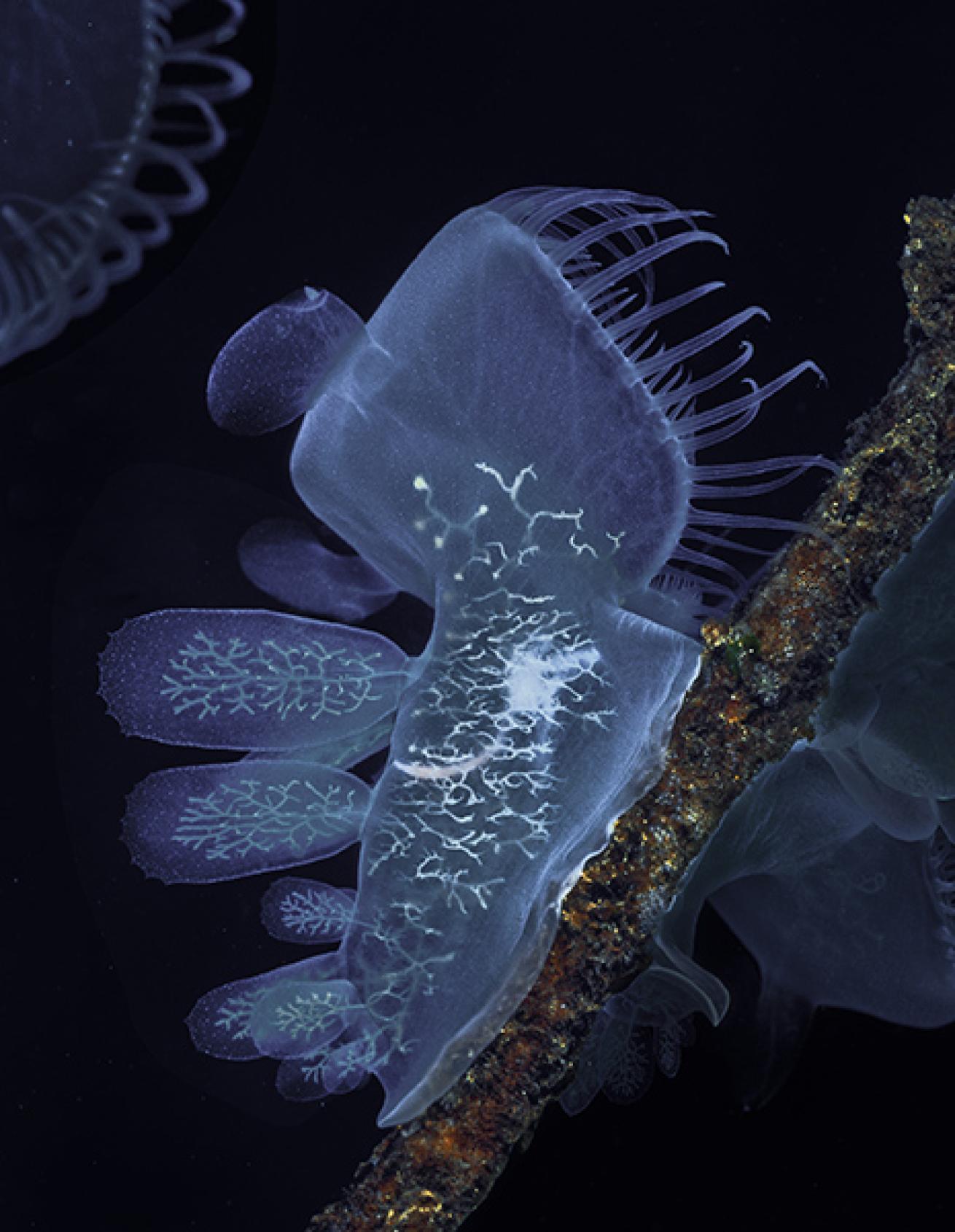

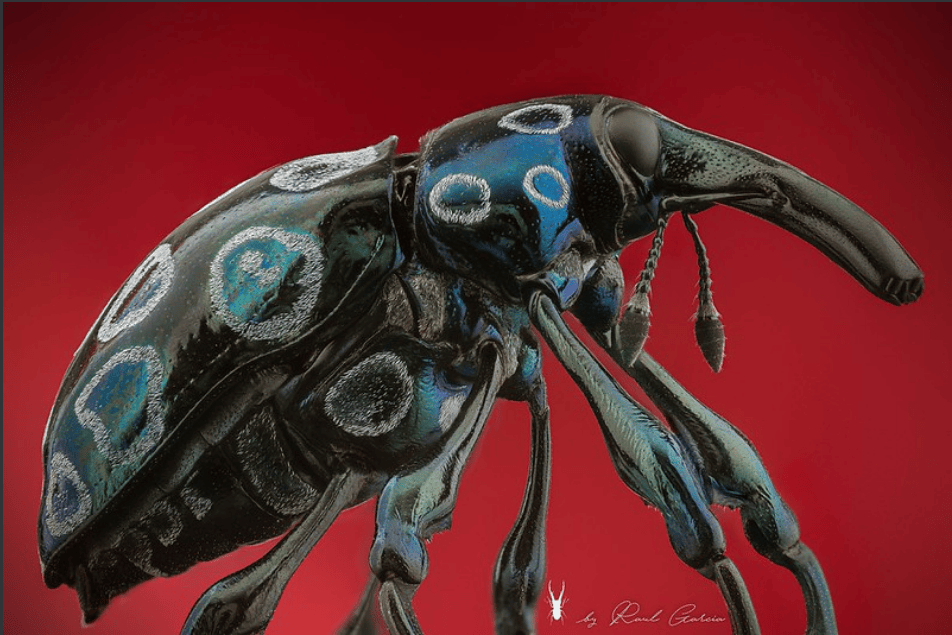

....and a rather spiffy pic!

photo by Ludovic