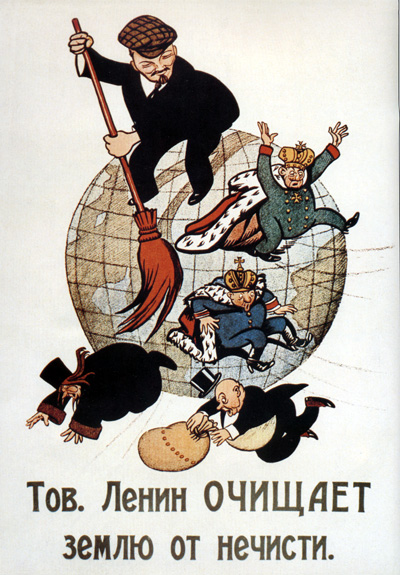

“The People are no longer afraid” was the cover of one of the newspapers published on the 12th of May of 1974. On April 25, 1974 a coup carried out by the Armed Forces Movement (MFA), in disagreement with the colonial war that had been going on for thirteen years in Mozambique, Angola and Guinea, put an end to the Portuguese dictatorship, which lasted 48 years under the direction of Antonio Salazar and under the leadership of Marcelo Caetano (after 1968).

Thousands of people immediately left their homes, against the appeal of the military who led the coup – which insisted on the radio for people to stay at home -, especially in Lisbon and Porto, and it was with the people at their front door, shouting "death to fascism”, that the Government was surrounded in the Quartel do Carmo (Barracks of Carmo) in Lisbon; the doors of the prisons of Peniche and Caxias were opened for release all political prisoners; PIDE / DGS, the political police, was dismantled; the headquarters of newspaper of the regime, The Age, was attacked and the censorship was abolished.

The Portuguese empire would fall later in 1974, after mobilizing nearly two million forced workers (in the mines in South Africa, cotton plantations in Angola, among others) and a 13 year war – 1961-1974 – to prevent the independence of the African countries of Angola, Cabo Verde, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau. Having been built to increase the profit of monopolies, as well as to discipline the workforce, the Portuguese dictatorship fell in the hands of the workers in April of 1974. A significant part of the property owners had to flee the country after the nationalizations which were meant to put an end to the workers’ control, which had become generalized starting February of 1975, especially in the banking sector, large metallomechanical factories, etc.

The ankylose structure of the empire – as well as that of its Bonapartist regime – led to the most important social rupture in post-war Europe – so great was the rupture and the length of it that no historian to this day has managed to determine how many workers’ meetings happened during the week after the coup by the MFA because there were hundreds, maybe thousands, and countrywide.

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- 📀 Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 🔥 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- ⚔ Come talk in the New Weekly PoC thread

- ✨ Talk with fellow Trans comrades in the New Weekly Trans thread

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

Death to middle management.

There's probably some good reading about how soviet technocrats tried to implement scientific measurement and optomization of factory work, and the various ways factory workers told them to knock it the fuck off, and maybe try to apply that to modern life or just share a moment of solidarity with workers long ago who were also telling their managers to take their stop-watches and shove them up their managerial asses.

One of my favorite experiments in this vein was when the Soviets tried to implement continuous work weeks to optimize production by breaking the calendar into 5 day chunks and randomly assigning everyone 1/5 days off. It was a disaster, everyone hated it primarily because there was no way to make your own day off line up with your friends and family, a lot of factories lied and said they were doing it while continuing to do the old schedule, and the experiment was canned after about a year and they went back to having a regular weekend (IIRC all of the Soviet experiments with changing the calendar ended by 1940).

I love reading about the push and pull between workers, management, central planning, and bureaucracy is the USSR. Shit's deliciously complicated and there's a lot of labor democracy that goes far beyond crass notions of striking workers and dictatorial management. To me, it seems like Soviet workers maintained a great deal of power throughout the history of the union, which flies in the face of all the propaganda.

Yeah imagine if some business school types cooked up this idea in America, if you weren't unionized your only recourse would be to flee to another company (if you even could!).

From what I understand they did, back in the 20s with Fordism and shit. And there was a lot of worker push-back that stopped some of it. The whole history of Fordism and it's spread around the world is cool stuff, the way it influenced labor and industry everywhere, and the ways, say, the fascists used it vs how the soviets used it vs how the americans used it. And there's probably something about it's legacy today, whether in clothing sweatshops in haiti or high-tech lights-out fabs that have finally replaced fallible human flesh with the eternal perfection of the machine