this post was submitted on 25 Jan 2024

24 points (80.0% liked)

C Programming Language

993 readers

1 users here now

Welcome to the C community!

C is quirky, flawed, and an enormous success.

... When I read commentary about suggestions for where C should go, I often think back and give thanks that it wasn't developed under the advice of a worldwide crowd.

... The only way to learn a new programming language is by writing programs in it.

- irc: #c

🌐 https://en.cppreference.com/w/c

founded 1 year ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

Firstly, I'm not sure where you got the impression that Rust is designed to replace C. It's definitely targetted at the C++ crowd.

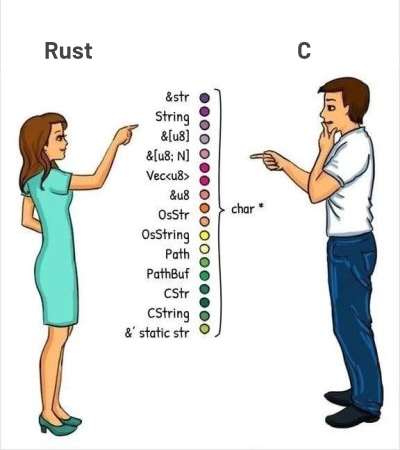

The string comparison with Rust actually points out one of my problems with C: All those Rust types exist for a reason - they should behave differently. That means that in C these differences are hidden, implicit and up to the programmer to remember. Guess who is responsible for every bug ever? The programmer. Let's go through the list:

&str - a reference to a UTF-8 string on the stack, hence fixed size.

String - a handle to a UTF-8 string on the heap. As a result, it's growable.

&[u8] - a reference to a dynamically sized slice of u8s. They're not even ASCII characters, just u8s.

&[u8;N] - a reference to an array of u8s. Unlike above they have a fixed size.

Vec - a handle to a heap-allocated array of u8s.

&u8 - a reference to a u8. This isn't a string type at all.

OsStr - a compatibility layer for stack-allocated operating system strings. No-one can agree on what these should look like - Windows is special, as usual.

OsString - a compatibility layer for heap-allocated OS strings. Same as above.

Path - a compatibility layer for file paths, on the stack. Again, Windows being the special child demands special treatment.

PathBuf - a heap-allocated version of Path.

CStr - null-terminated stack-allocated string.

CString - null-terminated heap-allocated string.

&'static str - a string stored in the data segment of the executable.

If you really think all of these things ahould be treated the same then I don't know what to tell you. Half of these are compatibility layers that C doesn't even distinguish between, others are for UTF-8 which C also doesn't support, and the others also exist in C, but C's weaker type system can't distinguish between them, leaving it up to the programmer to remember. You know what I would do as a C dev if I had to deal with all these different use cases? I would make a bunch of typedefs, so the compiler could help me with types. Oh, wait...

I dislike C because it plays loosey-goosey with a lot of rules, and not in an opt-in 'void*' kind of way. You have to keep in your head that C is barely more than a user-friendly abstraction over assembly in a lot of cases. 90% of the bugs I see on a day to day basis are integer type mismatches that result in implicit casts that silently screw up logic. I see for loops that don't loop over all the elements they should. I see sentinel values going unchecked. I see absolutely horrible preprocessor macros that have no type safety, often resulting in unexpected behaviour that can take hours or days to track down.

These are all problems that have been solved in other, newer languages. I have nothing personal against C, but we've had 40+ years to come up with great features that not only make the programmer's life easier, but make for more robust programs too. And at this point the list is getting uncomfortably long: We have errors as types, iterators, type-safe macro systems, compile-time code, etc.. C is falling behind, not just in safety, but in terms of ease of use as well.

Correction:

stris not really stack-allocated, it rather is a fat pointer (i.e. pointer + length) to a string somewhere (on the heap or in the binary).Edith: replaced heap with stack

I never said str is heap-allocated. I'm presuming you meant stack when you said heap (or you meant String when you said str)?

You're right, I meant stack.

stris not like anu8array, but a pointer.That's fair. Because I explicitly mentioned &'static str later on, my explanation of &str implicitly assumes that it's a non-static lifetime str, so it isn't stored in the executable, which would only leave the stack. I didn't want to get into lifetimes in what's supposed to be a high-level description of types for non-Rust programmers, though. I mentioned 'stack' and 'heap' explicitly here because people understand that they mean 'fast' and 'slow', respectively. Otherwise the first question out of people's mouths is 'why have a non-growable string type at all??'.

Thank you for your answer. I am not a professional C developer. I am learning it just for myself and have no production products written in C. And I can imagine how difficult is to support something really huge and commercial. Now C is more for hobby developing and tooling. But I know guys who are making desktop apps in C just for performance.

C is in no way "more for hobby developing and tooling". It's still foundational to compilers, language runtimes, and operating systems (the Linux kernel was, famously, exclusively written in C up until extremely recently, and the non-C parts are still optional). It's also the only supported language on many embedded devices.

My question when I see responses like this is: what genuinely useful new safety features have been added since Ada? It's ancient and has distinct types, borrow checking (via limited types), range types, and even fixed point types. I've always wondered what niche Rust is targeting that Ada hasn't occupied already. It feels like devs decided that safety was important, c/c++ are too unsafe, need a new language; without ever having looked to see if such a language exists?

I haven't used Ada myself, but I have heard it brought up before. One of the huge advantages Rust has is it's packaging, versioning and build system. I'd argue this is second to none.

Rust is GPL licensed. As I understand it, licensing was a major blocker for Ada and potentially hampered it's uptake in the past.

Rust has modern sensibilities, like first-class iterator support, or built-in UTF-8 strings, etc.. It also has a lot more of a functional style, rather than procedural.

More subjectively, Ada's syntax looks very... unflattering to my eyes. I much prefer Rust in that regard. Looking at Ada reminds me of my time with VHDL, which is never a flattering comparison.

Ada actually found itself implementing Rust's ownership and borrowing system, as pointers were not formally verifiable using SPARK before, so Rust must be doing something right!

Ada is still "new" compared to C, so I suspect the OP would have similar problems with it.

The question of what advantages Rust has over Ada is a good one, but I think it's been pretty well discussed already. Just a quick google for "Rust vs Ada" turns up lots of discussions.

I don't know Ada, and I love Rust, but it seems entirely plausible that the reasons for Rust's greater popularity is primarily social rather than technical. Before I learned about Rust, my impression from talking to more experienced C++ programmers was that Ada was an interesting language with good ideas that was ruined by being "designed by committee." Rust is at least the third major attempt to design a language specifically to draw some of C++'s user base, the other two being D and Ada (there are other examples that are more debatable; e.g. Erlang and Nim). But hey...at least one of them is finally gaining some ground!

yeah if there's a popular "modern replacement for C" it'd be Go, similar procedural syntax with some functional features + great stdlib + static linking by default + easier concurrency + GC, but the new memory arenas feature looks like they're open to change and it's moving away from that dumbed down language for Google's junior devs it used to be known as

I find Go a joy to maintain long term due to the high readability and stability of the language and standard libraries. In that respect I guess it isn't that dissimilar to classic languages like C or Pascal which can be used to write systems that are maintainable for many years.

On the downside Go has some questionable design decisions. Null pointers and multi-value result, err returns are the result of an inadequate type system. It should not be impossible to dereference a null pointer or access the result if there is an error. With discipline problems don't crop up that often but this is a solved problem in language design and pushes work onto the programmer that should be handled in the language.

Even with such serious deficiencies Go is still arguably one of the better alternatives to dynamic language like Python of Javascript and gets you most of the benefits of static languages without too much complexity. Having a runtime and garbage collection prevents Go use in libraries consumed by C and other languages and the overhead for calling into C is high. That disqualifies it as a modern C replacement.

The more I play with Zig, the more I like it. I don't think I could use it for anything I had to support at the moment. Realistically you are forced to develop live at head. Active third party dependencies often won't compile against stable versions. There aren't a lot of native libs yet but it really feels like it inherits all of C. There is a lot of stuff to like but it will be a more compelling language when it stabilizes.

I hated the first nine words of this comment, but agree with everything else

Zig also seems interesting. I'm definitely a fan of what I've seen of their error handling. Intercompatibility with C (no FFI required) also sounds tempting, especially if I already had a legacy C codebase I wanted to migrate.